50%

Resilient Cities Index

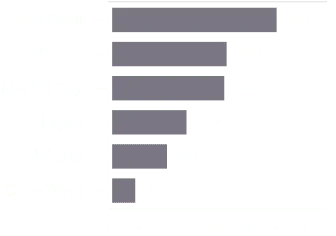

To support policymakers and stakeholders to understand risk and design effective policies, Economist Impact developed a benchmark of 25 cities. To gauge their resilience, we took measurements across four pillars: critical infrastructure, environment, socio-institutional and economic. Economist Impact has defined urban resilience as a city’s ability to avoid, withstand and recover from shocks and long-term stresses. A resilient city should be able to self-organise following a shock event, adapt to unfolding risks and plan ahead rather than react.

Cities have long been celebrated as symbols of resilience, endurance and adaptability.

They are often regarded as dynamic and progressive powerhouses, brimming with opportunities, innovation and vitality. It is the representation of opportunity, in particular, that continues to pull people towards urban centres in droves.

By 2050, cities across the world will become home to more than two-thirds of the world’s population.

It will therefore become critical for societies and governments to evaluate their current risk management practices and build resilient cities that can withstand an uncertain future.

To support policymakers and stakeholders to understand risk and design effective policies, Economist Impact developed a benchmark of 25 cities.

To gauge their resilience, we took measurements across four pillars: critical infrastructure, environment, socio-institutional and economic.

Explore the Resilient Cities Ranking

The Resilient Cities Index

Explore the rankings below

Map View

Chart View

The index interprets critical infrastructure as—energy, water, transportation, buildings and digital connectivity. Together they help to meet the everyday needs of residents, withstand extreme events and support cities in bouncing back in post-disaster scenarios.

Environment resilience is considered along six aspects in this index: flooding, heat stress, air pollution, disaster management, decarbonisation and waste management. Rapid urbanisation and climate change together are exacerbating the environmental threats to cities. From grappling with extreme heat and rising sea levels to hazardous air and mounting rubbish, our index shows a mixed picture when it comes to building environmental resilience.

This measures indicators including digital government platforms, crime and safety, income inequality, and social protection. Taken together, these can affect the degree to which a society can withstand disaster and volatility and bounce back.

Cities are engines for broader economic growth, and access to opportunity has been the dominant driver for growing urban migration over the last half century. The economic pillar considers the economic exposure and robustness of a city along with its capability to innovate and its quality of human capital.

Key findings

The top four cities in this pillar are Dubai, Shanghai, New York and Singapore; capital-rich market locations able to better develop new infrastructure when compared with cities in Europe that are constrained by decades- or century-old systems. Within this pillar, digital infrastructure along with transportation are a drag on resilience.

Patchy internet quality, which can impede access to digital services, pulled down the overall resilience score in the critical infrastructure pillar. Smart technologies and advanced data analytics can help predict risks and optimise existing systems. However, greater digitalisation comes with risks, especially to critical infrastructure, which most cities in the index have built safeguards against.

Only a few cities in the index manage to achieve high scores in future-proofing, which involves ensuring infrastructure preparedness for shocks while managing current and future emissions. One way that cities can future-proof is by incentivising sustainable designs in buildings, a practice only found in high-income cities in the index.

Cities are employing a variety of nature-based solutions to adapt to flooding and heat stress, from planting rooftop vegetation and mangrove forests (green infrastructure) to rehabilitating wetlands (blue infrastructure). Cities are also decarbonising by adopting renewable energy and negative emission technologies, such as carbon capture, storage and removal. However, the scalability of these technologies is likely to be challenging for resource-constrained emerging market cities.

Only nine cities have a single comprehensive plan to support vulnerable groups. However, one bright spot is that cities promote a culture of readiness to act in case of a disaster. The majority of cities scored highly on this or are working to improve their readiness.

The low penetration of financial safety nets hinder safeguards to threats and undermine a city’s ability to resume and recover from shocks. Incubating innovation, which can foster solutions for long-term resilience, is also lagging, with most cities performing poorly in their start-up ecosystems.

Critical infrastructure

Newer cities built on modern greenfield infrastructure lead the way as European cities struggle with legacy infrastructure.

Back up or black out

Municipality utility infrastructure management is an issue across all cities. Substantial capital should support the overhaul and upgrade of aged systems.

Cities also need to identify the most effective and affordable interventions to close the energy deficit. Mini-grids can help close the energy access gap in hard-to-reach areas—14% of Bangladesh’s population use solar home systems. Addressing energy poverty will protect the vulnerable during extreme weather events.

Back up or black out

Management of critical infrastructure continues to be a problem for the developing world. More than 107 million people in cities covered in our index live with inadequate electricity provision, which can cause interruptions to daily lives and amplify the impacts of a disaster while responding to a crisis.

New Delhi

32.1M

32.1M

New Delhi, India

Dhaka

22.5M

22.5M

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Mexico City

22.1M

22.1M

Mexico City, Mexico

Lagos

15.4M

15.4M

Lagos, Nigeria

Jakarta

11.1M

11.1M

Jakarta, Indonesia

Cape Town

4.8M

4.8M

Cape Town, South Africa

107M

Back up or black out

Municipality utility infrastructure management is an issue across all cities. Substantial capital should support the overhaul and upgrade of aged systems.

Cities also need to identify the most effective and affordable interventions to close the energy deficit. Mini-grids can help close the energy access gap in hard-to-reach areas—14% of Bangladesh’s population use solar home systems. Addressing energy poverty will protect the vulnerable during extreme weather events.

Management of critical infrastructure continues to be a problem for the developing world. More than 107 million people in cities covered in our index live with inadequate electricity provision, which can cause interruptions to daily lives and amplify the impacts of a disaster while responding to a crisis.

More than 107 million people in cities covered in our index live with inadequate electricity provision.

Cities must adapt to what they can’t avoid

Cities will continue to face unprecedented economic, social and health impacts from deadly heat, frequent flooding and filthy air.

Future-proofing infrastructure is critical to reduce the impacts of extreme weather events. Singapore has adopted green roofs and corridors to reduce heat impacts. Such solutions reduce air temperature by 1 to 2 degrees Celsius while providing shade from the heat.

Environment

Future-proofing against environmental disasters will draw on innovative solutions, requiring capital and long-term thinking.

Managing and mitigating climate risks

The cities in our index face different water risks. Cities globally are being tested on their ability to evaluate, learn and adapt to the evolving risks associated with water and driven by climate change. Responding to the risk will require investments in infrastructure, governance, human capital and communication.

Dhaka, Jakarta and Shanghai have experienced incessant storms and rain this year, inducing floods.

The cities in our index face different water risks. Cities globally are being tested on their ability to evaluate, learn and adapt to the evolving risks associated with water and driven by climate change. Responding to the risk will require investments in infrastructure, governance, human capital and communication.

Bangkok, Dhaka and Jakarta have experienced incessant storms and rain this year, inducing floods.

Riverine flood risk

Coastal flood risk

Score 0-4 denotes the proportion of people expected to be impacted by riverine flooding where a score of 4=least resilient and most likely to be impacted

Score 0-4 denotes the proportion of people expected to be impacted by coastal flooding where a score of 4=least resilient and most likely to be impacted

Managing and mitigating climate risks

The cities in our index face different water risks. Cities globally are being tested on their ability to evaluate, learn and adapt to the evolving risks associated with water and driven by climate change. Responding to the risk will require investments in infrastructure, governance, human capital and communication.

Dhaka, Jakarta and Shanghai have experienced incessant storms and rain this year, inducing floods.

Riverine flood risk

Score 0-4 denotes the proportion of people expected to be impacted by riverine flooding where a score of 4=least resilient and most likely to be impacted

The cities in our index face different water risks. Cities globally are being tested on their ability to evaluate, learn and adapt to the evolving risks associated with water and driven by climate change. Responding to the risk will require investments in infrastructure, governance, human capital and communication.

Bangkok, Dhaka and Jakarta have experienced incessant storms and rain this year, inducing floods.

Coastal flood risk

Score 0-4 denotes the proportion of people expected to be impacted by coastal flooding where a score of 4=least resilient and most likely to be impacted

Early warnings for all

One-third of the global population is still not covered by early warning systems.

Early warnings for all

Just 24 hours warning of a coming storm or heatwave can cut the ensuing damage by a third. And spending US$800m on such systems in developing countries could avoid losses of US$3bn-16bn a year.

Socio-institutional

Whatever the shock, the vulnerable are more impacted. Cities perform relatively worse in the socio-institutional pillar due to income inequality, and under performing health and well-being metrics.

“If you’re poor, you can’t move away from flood risk. If you rent, you can’t necessarily make changes to your home to make it safer. If you’re isolated, you are less likely to survive a heatwave.”

Fiona TwycrossDeputy mayor for fire and resilience, Mayor of London

A culture of readiness

Data captured is based on an evaluation of awareness campaigns in a city towards developing cultural readiness.

A strong culture of readiness can help prepare a population for anything.

High performers include clear, comprehensive and detailed information in their action plans.

The culture of readiness of emerging cities varies. New Delhi and Mexico City show progress is possible in less affluent economies.

The Delhi Disaster Management Authority conducts disaster awareness campaigns across various media channels, runs mock drills and provides measures for safe action for before, during and after events like fires, floods and earthquakes.

Economic

Turning cities' ambitious resilience goals into action calls for a stable economic environment and a vibrant innovation ecosystem.

Urban innovation ecosystems

The level of business innovation in the city is based on factors such as performance, fundings, market reach, connectedness, talent and experience and knowledge. Data was sourced from the Startup Ecosystem Report, 2023.

Note: This graph presents scores of the top 15 cities.

Wide gaps exist across cities in creating an innovation ecosystem that can foster cutting-edge solutions to the most pressing problems.

Emerging cities like Shanghai and New Delhi outperform the majority of high-income Western cities in creating an innovation ecosystem.

An innovative business ecosystem encourages businesses and industries to adapt to changing market conditions and can lead to solutions that promote a city’s resilience. The ability to adapt will help businesses withstand shocks and maintain a competitive edge. But cities will have to invest heavily in human capital to empower its workforce with skills that can prepare them for a fast changing economic landscape.

Emerging cities, Shanghai and New Delhi, outperform the majority of high-income Western cities in creating an innovation ecosystem.

Conclusion:

Resilience in motion

Cities are places of movement, flow and energy; rarely static. They can also be sites of debilitating natural and human shocks and stresses, which can have an outsized impact on critical infrastructure, residents’ livelihoods and a city’s social fabric. To become more capable of absorbing these adverse shocks, whether they be natural, economic or social, cities need to become more resilient.

Key takeaways

This is contingent on the democratisation of information. All city-dwellers should have equal access to government information, including what to do in an emergency. Recognising that information is key, municipalities could consider partnering with a digital platform to minimise misinformation and ensure the city moves in one direction, despite disruption.

Cities are nothing without the people who inhabit them. Greater attention to social cohesion will help to ensure cities are less fragmented, adaptive and better prepared for shocks. City governments should overlay resilience efforts with initiatives that aim to improve the lives of urban residents. This process should be driven by city leadership and engage civil society.

National governments and municipality leaders will have to collaborate to ensure universal early warning systems coverage by 2027. There are two challenges that need to be met: the investment gap and policy discrepancy. Community acceptance and responsiveness to early warnings are essential for their effectiveness. This can be achieved through systematic training and education and awareness programmes.

Providing clear incentives for businesses and individuals to prepare for future risks can help to build the necessary defences. These could take the form of financial benefits to retrofit legacy infrastructure or rewards for meeting benchmarks on the use of renewable materials.

An iterative process ensures that interventions remain effective in the face of evolving challenges such as climate change and urbanisation. Cities can also identify the gaps and make data-driven decisions. Tracking progress will also keep city officials accountable and help ensure that public funds are used efficiently and transparently, maintaining the trust among citizens

Cities that provide an enabling environment where start-ups, businesses and research centres can develop cutting-edge solutions will be better able to tackle complex problems. Technology will also help to identify, predict and monitor risks, which is critical to building resilience.

“A resilience strategy is not something developed at a desk by a city official. Cities need to bring a variety of stakeholders together, including community representation, the poor and the vulnerable."

Katrin Bruebach, global director of programmes, innovation and impact at the Resilient Cities Network.

Read

report

The Resilient Cities Index report combines index analysis with expert commentary to identify patterns, common strengths, deficits and best practices across 25 global cities.

Read report

Watch

video

Asian cities like Bangkok, Hong Kong, Jakarta and Dhaka urgently need to become more resilient to the effects of climate change. Watch the explainer video for more insights.

Watch video

Custom content is written, produced or curated by either a sponsor or by EI Studios, the custom division of Economist Impact. Such placements are clearly labelled as Advertisement, Advertisement feature, Sponsored content, Sponsor perspective, or words to that effect wherever they appear on our website or apps. Neither The Economist news and editorial team, nor Economist Impact’s independent experts, have any involvement in the creation of this content.

Explore further

Accelerating progress for good

Paradoxically, innovations that build resilience can also bring new risks to the fore. Brad Irick, chief executive of Tokio Marine Kiln, an insurer, explains how his firm supports technology and practices that are making society stronger.

Delivering the true value of insurance

You will only know the quality of your insurance policy when you need it most. Masahiro Ota, head of claims at Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance, shares how his company is working to protect its customers even better and help rebuild their lives after disasters.

Standing with customers in times of need

Tokio Marine believes insurance has two critical roles: to give people confidence to overcome the unexpected, and to help solve society’s biggest issues. In an interview with Satoru Komiya, the group’s chief executive, we hear how the insurer is working to develop a resilient and sustainable society.